Haliburton Native Plants Explained

An in-depth look at the benefits of native plants, how we decide what’s native to Haliburton County, and a list of plants considered native.

Table of contents

What are native plants?

What is the difference between a native plant, a non-native plant and an invasive plant? And how are native plants beneficial to nature and to ourselves?

Definition of a native plant

We hear the term “native plant” a lot, but what exactly is one? Here at Grounded we define it as a plant that has co-evolved with other organisms in its community. In practice, that means it has been living in a region for thousands or millions of years, is well adapted to that region and fulfills a role in that region’s ecology.

Native plants are often said to be those that were in North America before European settlement. This makes a lot of sense, as many plants of Eurasian origin were brought here by Europeans, often for use in agriculture. More recently, the horticulture industry has introduced non-native plants, some of which have become invasive.

The benefits of native plants vs. non-native plants

Native plants are beneficial to natural ecology and to gardeners. Having co-evolved with other organisms, native plants are better able to fill an ecological niche. This helps maintain biodiversity – for example, a pollinator might specialize in extracting pollen from a particular plant species. If that plant isn’t present, that pollinator dies out, which in the inter-related web of organisms could have an effect that extends beyond those two species.

Non-native plants, which have not co-evolved with other local species, don’t necessarily fulfil that role. While some more generalist pollinators and other wildlife might benefit from the presence of non-native species, specialist species might not. This leads to a location facing reduced biodiversity and becoming less resilient to stress.

The most significant study into this looked at Carolina Chickadees. The paper by Desirée L. Narango, Douglas W. Tallamy, and Peter P. Marra found that when nonnative plants increased, both insect availability and chickadee population growth declined. It also found that populations could only be sustained if nonnative plants constituted less than 30% of plant biomass.

Our results reveal that properties landscaped with non-native plants function as population sinks for insectivorous birds. To promote sustainable food webs, urban planners and private landowners should prioritize native plant species.

Desirée L. Narango, Douglas W. Tallamy, and Peter P. Marra, Nonnative plants reduce population growth of an insectivorous bird (2018) See paper here.

When it comes to the needs of the gardener, native plants are in general better suited to the place in which they will be grown. A gardener will not need to amend soil or enhance irrigation, for example, if a plant is well matched to its location. The native plant has the opportunity to become part of an ecology in the garden, which leads to lower maintenance requirements.

Finally, a native plant gives the gardener a better sense of place. With some non-native plant species sold across North America, there’s the danger that a garden in Haliburton looks like one in Chicago. Native plants make a garden feel like “here”.

Definition of an invasive plant

An invasive plant, such as Garlic Mustard or Bindweed, is one that is non-native and has a tendency to spread to a damaging degree. This can happen when the plant has no natural predators or control mechanisms in its environment. It can then outcompete native species, reducing biodiversity and the ability of an ecosystem to function. You can find a list of Ontario invasive plants here. We advocate for the removal of invasive plants if you find them in your garden.

Deciding which plants are native to Haliburton County

The journey towards defining which plants are native to Haliburton County starts by looking at the land. Here are several ways to narrow down what’s native – and what’s not.

Forget climate zones

Gardeners have long used plant hardiness zones to find out if a plant will survive a Haliburton winter. Haliburton County is generally considered to be in Zone 4.

When working with native plants, hardiness zones become less relevant. There are two reasons for this. First, if a plant is native to here, it goes without saying that it is winter-hardy. Second, hardiness zones extend beyond any particular location. While Haliburton County sits in Zone 4, so do parts of Saskatchewan and Newfoundland. The plants native to these three locations are likely to be very different.

The ecoregions of Ontario

Instead of hardiness zones, we use the Ontario ecological land classification framework. This divides the province into areas that have common features, such as bedrock geology or climate. We ask: what plants are native to these zones?

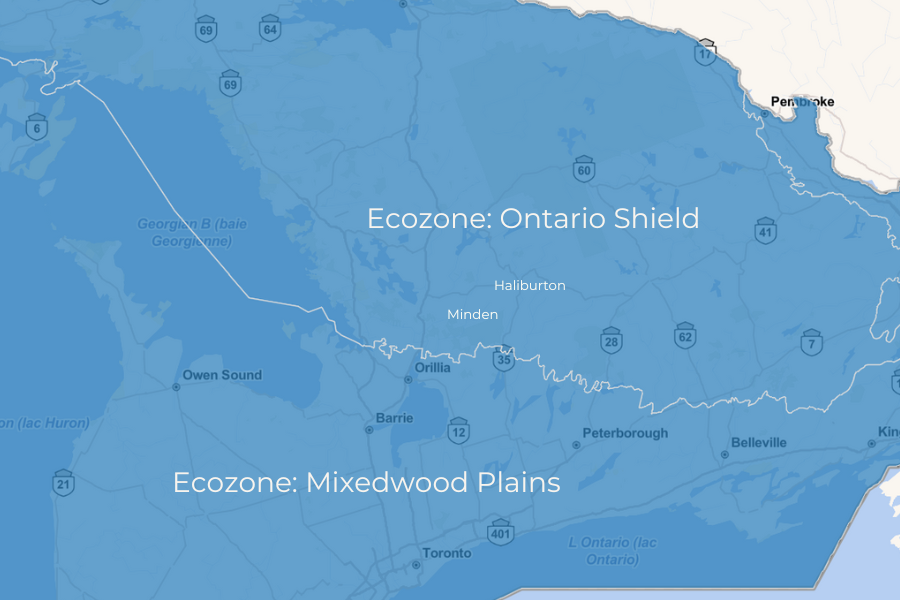

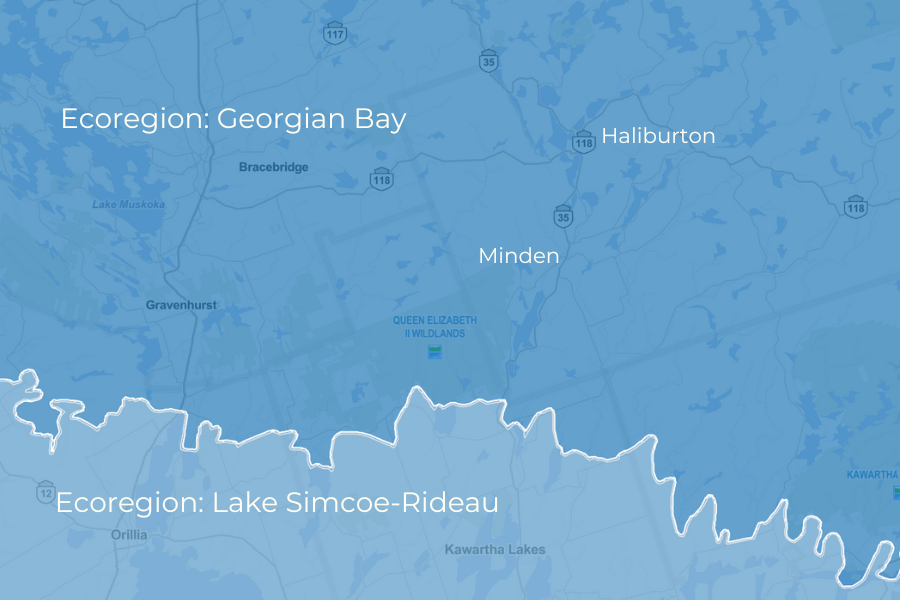

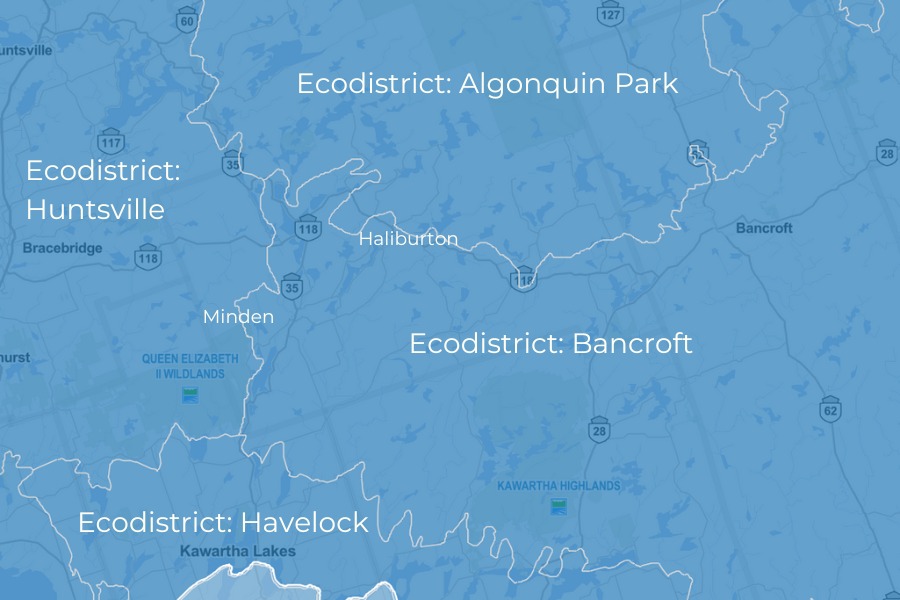

There are several layers of classification. At the largest scale are Ecozones (shown with red borders on the map below), followed by Ecoregions (black borders) and Ecodistricts.

Where Haliburton County sits within the Ecological Land Classification

If you’re eagle eyed, you might have noticed on the map above that one of the thick red lines between Ecozones comes awfully close to Haliburton County. This fact gives us the greatest difficulty – and also the greatest opportunity – when choosing plants for here. This will become clearer as we continue.

Let’s look at the maps more closely. Below is a map showing the border between two ecozones relevant to Haliburton County: Mixedwood Plains in the south and Canadian Shield in the north. If you’ve driven north from Toronto to Haliburton County, you’ve no doubt seen the landscape and its vegetation change as you cross into the Shield. Haliburton County is right on the edge of two Ecozones – the largest classification size.

Now let’s zoom in a little. Here are the Ecoregions.

And here we zoom further, to the Ecodistricts.

A close-up look at Haliburton County

Once we get to the Ecodistrict level, we can see Haliburton County falls within more than one.

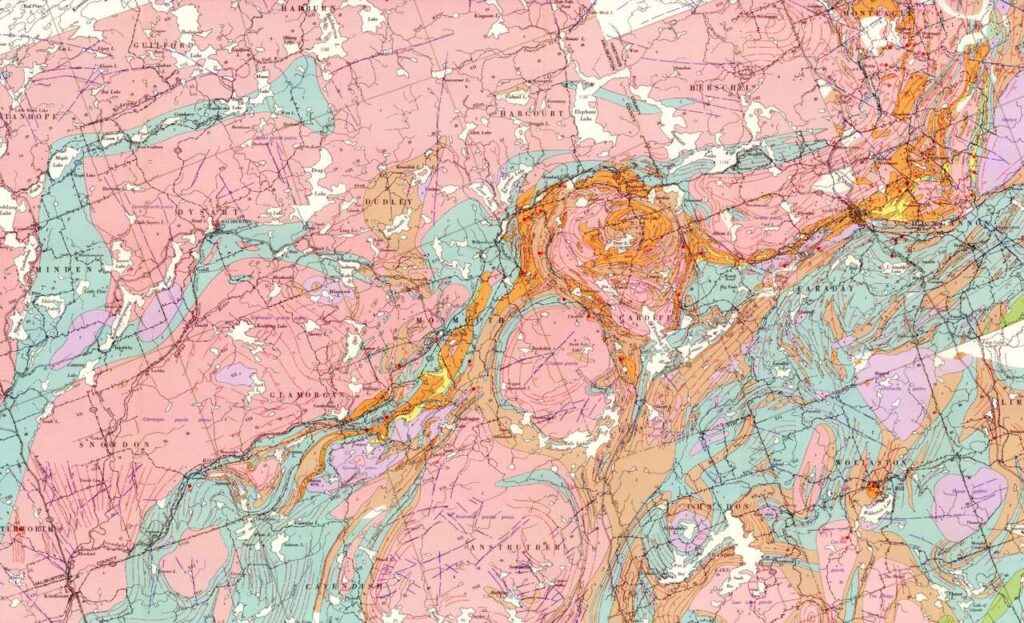

Here’s another map to look at: the geology of the area. Most of the map is pink – granite. But look at those turquoise fingers – they’re limestone or dolomite. Is is possible the gardens in those areas (for example Minden all the way through Maple and Eagle Lakes, or Minden through Ingoldsby to the south part of Haliburton village, or the area around Wilberforce, or the path of Highway 503 from Tory Hill to Furnace Falls) might have different conditions for plants?

The Land Between

Let’s forget about about the Ecological Land Framework for a minute and look at another definition of our region: The Land Between. This is a sausage of land spanning from Parry Sound in the west to the Ottawa Valley in the east, with its northern boundary north of Haliburton village and its south touching Orillia and Peterborough.

It sits between the Canadian Shield and the St Lawrence Lowlands and as such is one massive ecotone – a boundary area between very different ecological districts. Its patchwork, which contains elements of the Shield and Lowlands, is extremely biodiverse – as is common among ecotones. Those fingers of limestone we saw in the geological map above is perhaps evidence of this. Take a look at this fascinating interactive map to learn more.

If we’re going to choose native plants based on a geographic district, we can do a lot worse than choose those native to The Land Between.

The habitats of Haliburton County

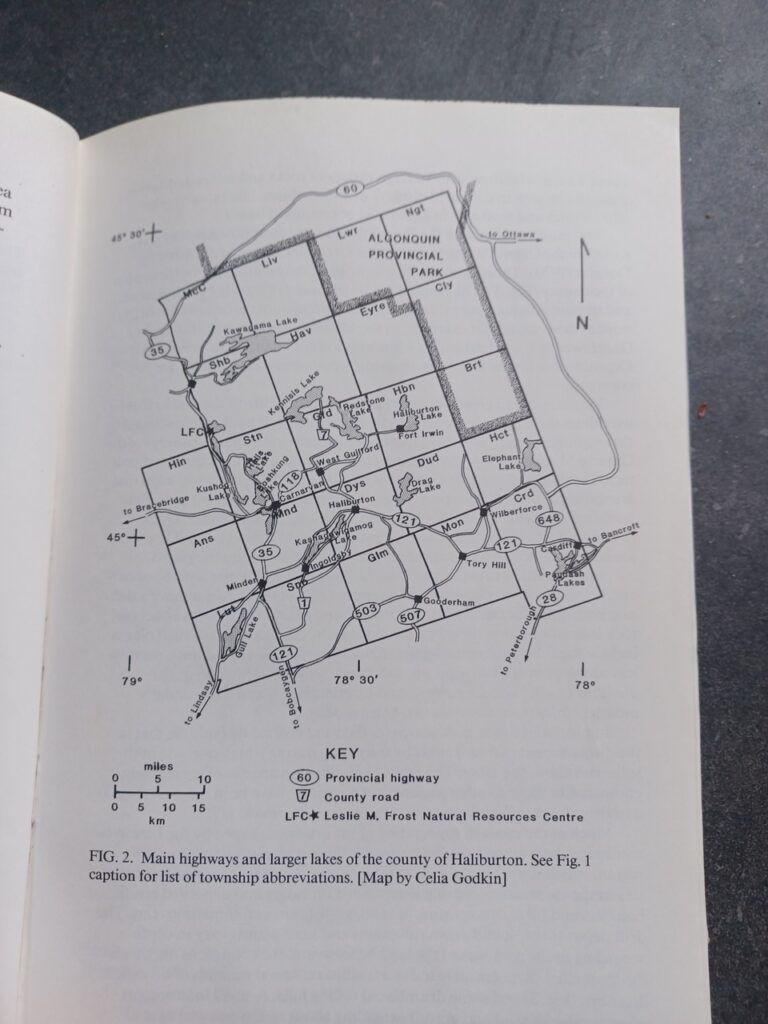

Zooming further into Haliburton County, let’s look at its various natural habitats. A great place to start is a book published in 1990: Haliburton Flora: An Annotated List of the Vascular Plants of the County of Haliburton, Ontario, by Eleanor G. Skelton and Emerson W. Skelton. You can read it for free online here or get it at the library here.

The book was a labour of love for this husband and wife team. As the book’s foreword says:

For eight years, from 1976 to 1983, the Skeltons rented a cottage in Haliburton, sometimes departing from the city as early as April and returning to Toronto at Thanksgiving. They conducted field excursions, collecting and carefully pressing plant specimens throughout the growing seasons.

Foreword by Sheila McKay-Kuja, to Haliburton Flora: An Annotated List of the Vascular Plants of the County of Haliburton, Ontario, by Eleanor G. Skelton and Emerson W. Skelton

The book documents the County’s topography, drainage and roads, its rocks and glacial deposits, its soils, and its climate.

It also defines its forests:

Forests within the county are composed predominately of mixed coniferous and deciduous tree communities, which vary in composition according to the topography of the land (e.g., ridges,

Haliburton Flora: An Annotated List of the Vascular Plants of the County of Haliburton, Ontario, by Eleanor G. Skelton and Emerson W. Skelton

valleys, slopes, or wetlands) and the tolerances of species for particular soil and moisture conditions.

Wetlands:

Owing to the topography of the land, with its many depressions and valleys, and to the plentiful supply of rainfall, numerous wetlands occur in the county of Haliburton. Melting snow, rainfall, and groundwater supply these wetlands, which release the water slowly throughout the season, thereby providing habitats for aquatic and semiaquatic plants as well as breeding and feeding grounds for birds and mammals.

Haliburton Flora: An Annotated List of the Vascular Plants of the County of Haliburton, Ontario, by Eleanor G. Skelton and Emerson W. Skelton

Anyone familiar with Haliburton County knows the vast majority of the land is forest, wetlands and open water (lakes). This causes challenges when matching native plants to human-created open areas, as we will see below.

The complex picture

We live in a world shaped by humans. We need to recognize that Haliburton native plants are affected by humans, too.

How human activity affects Haliburton’s native plant selection

We can’t ignore the impact human activity has had on the ecology of the area. From the extensive logging through to the development of towns and the construction of cottages on lakes, humans have caused disturbance. Many non-native species have become naturalized. Others have become invasive.

However natural we try to make our gardens, they will never be the kind of nature that existed here 200 or 2,000 years ago. Changes we make to lakefronts to build a cottage alter the hydrology and the makeup of species. The land over our septic beds arrests ecological succession. Our gardens are not typical of the landscape here, where trees would over time replace herbaceous perennial and shrubs.

The garden at Lucas House, which I am creating in Haliburton village, is a case in point. The house was built about 115 years ago and was until 2023 surrounded by lawn. The area has seen decades of disturbance, from the construction of the building to the widening of roads and the felling of trees. This is far from the maple-beech forests for which the area is known. The garden I am creating will not be a woodland garden: that would be impossible so close to the building. Instead, it will be mainly perennials, a kind of meadow or an artificial woodland clearing. It will contain plants native to Haliburton County but also others native to further south in The Land Between. The plants themselves were brought in from south of Peterborough. It’s an ecosystem, but it’s not 100% natural Haliburton. It has human influence.

About novel ecosystems

Some argue that our gardens and some other human-made landscapes should be considered “novel ecosystems”. These are ecosystems that don’t necessarily relate to those that pre-existed human activity, containing non-native as well as native species, and yet being able to function as ecosystems without constant human maintenance. The term is up for debate, but there is no doubt that humans have profoundly influenced the ecology of the planet.

The effects of climate change

Another factor we need to consider is climate change. We’re already noticing its effects. What effects are yet to come as, for example, warmer winters change the composition of our flora? Should we as humans help by introducing more plants from further south, or are we in danger of creating more problems? It’s a practical and ethical problem.

Finding native plants in Haliburton County

Here’s one final factor that affects those of us choosing native plants for our gardens and shorelines: can we find the ones we want?

Most vendors of native plants are based south of here, either around Peterborough or around the GTA. While they try hard to have an excellent section of species, they’re not necessarily focused on the needs of Haliburton County, especially if we’re looking for specialist rather than generalist species.

A related wrinkle concerns ecotypes. Ecotypes, or genotypes, relate to the genetics of a plant, which can vary from location to location. A plant that is native to a large part of the continent could have slightly different genetics that have evolved to help it compete in specific areas. That means a plant sourced from outside our Ecozones might not perform as well as one sourced from here.

There’s hope that life will get easier for us gardeners and the Haliburton native plants we tend. With the increasing popularly of native plants, growers such as Haliburton Micromeadows are popping up. I hope they will provide plants uniquely suited to this area using seeds gathered from this area.

Native plants for Haliburton County

Let’s get down to details. What are the typical trees and plants native to Haliburton County?

The place I started was the Skelton and Skelton book. It lists hundreds of species, each with details of its habitat and where it was found. Some of the plants were common; most were rare. With the book now almost 35 years old, the list needs editing.

Here, thanks also to guides from the Haliburton Master Gardeners, The Land Between and my own research, is a list of plants I believe can be considered native to Haliburton County and The Land Between.

Grasses

Side Oats Gramma

Blue Joint Grass

Bluejoint Grass

Poverty Oat Grass

Canada Wild Rye

Bottlebrush Grass

Sweet Grass

Indiangrass

Praire Dropseed

Bouteloua curtipendula

Calamagrostis canadensis

Calamgrostis canadensis

Danthonia spicata

Elymus canadensis

Elymus hystrix

Hierochloe odorata

Sorghastrum nutans

Sporobolus heterolepis

Sedges

Golden Sedge

Bebb’s sedge

Graceful Sedge

Long-stalked Sedge

Plantainleaf Sedge

Broad-leafed Sedge

Quill Sedge

Fox Sedge

Carex aurea

Carex bebbii

Carex gracillima

Carex peduculata

Carex plantaginea

Carex platyphylla

Carex tenera Carex

vulpinoidea

Ferns

Maidenhair Fern

Ostrich Fern

Sensitive Fern

Cinnamon Fern

Royal Fern

Christmas Fern

Bracken Fern

Adiantum pedatum

Matteuccia struthiopteris

Onoclea sensibilis

Osmunda cinnamomea

Osmunda regalis

Polystichum acrostichoides

Pteridium aquilinum

Herbaceous perennials (forbs)

American Sweet Flag

Pearly Everlasting

Canada Anemone

Spreading Dogbane

Canadian Columbine

Wild Ginger

Common Milkweed

Swamp Milkweed

White Turtlehead

Common Boneset

Large-leaved Aster

Spotted Joe-Pye Weed

Wild Strawberry

Creeping Wintergreen

Water Avens

Blue Flag Iris

Cardinal Flower

Square-stemmed Monkeyflower

Beebalm

Black-eyed Susan

Green headed Coneflower

Canadian Goldenrod

Heart-leaved Aster

Heath Aster

New England aster

Foam Flower

Blue vervain

Narrow-leaved Verbain

Common Blue Violet

Acorus americanus

Anaphalis margaritacea

Anemonastrum canadense

Apocynum androsaemifolium

Aquilegia canadensis

Asarum canadense

Asclepias syriaca

Asclepias incarnata

Chelone glabra

Eupatorium perfoliatum

Eurybia macrophylla

Eutrochium maculatum

Fragaria virginiana

Gaultheria procumbens

Geum rivale

Iris versicolor

Lobelia cardinalis

Mimulus ringens

Monarda didyma

Rudbeckia hirta

Rudbeckia laciniarta

Solidago canadensis

Symphyotrichum cordifolium

Symphyotrichum ericoides

Symphyotrichum novae-angliae

Tiarella cordifolia

Verbena hastata

Verbena simplex

Viola sororia

Shrubs

Smooth Serviceberry

Bearberry

Black Chokeberry

Bunchberry

Red Osier Dogwood

Bush Honeysuckle

Virginia Creeper

Common Ninebark

Canadian Plum

Chokecherry

Staghorn Sumac

Smooth Rose

Swamp Rose

Pussy Willow

American Elderberry

Elderberry

Meadowsweet

Spirea Alba

Nannyberry

Highbush Cranberry

Amelanchier laevis

Arctostaphylos uva-ursi

Aronia melanocarpa

Cornus canadensis

Cornus sericea

Diervilla lonicera

Parthenocissus quinquefolia

Physocarpus opulifolius

Prunus nigra

Prunus virginiana

Rhus typhina

Rosa blanda

Rosa palustris

Salix discolor

Sambucus canadensis

Sambucus canadensis

Spiraea alba

Spiraea latifolia

Viburnum lentago

Viburnum trilobum

Trees

Balsam Fir

Striped Maple

Red Maple

Sugar Maple

Speckled Alder

Yellow Birch

White Birch

Eastern Red Cedar

Tamarack

White Spruce

Black Spruce

White Pine

Black Cherry

Red Oak

Pussy Willow

Eastern White Cedar

Abies balsamea

Acer pensylvanicum

Acer rubrum

Acer saccharum

Alnus incana

Betula alleghaniensis

Betula papyrifera

Juniperus virginiana

Larix laricina

Picea glauca

Picea mariana

Pinus strobus

Prunus serotina

Quercus rubra

Salix discolor

Thuja occidentalis

This is still a very long list. And not all of these plants will be suitable for a garden situation, nor will be available from a native plant nursery. For that reason, I have further curated this list. You can see my list, which includes plant descriptions, here.

Conclusion

What conclusions can we draw from all this? And how can we move forward as we create our own garden or naturalized shoreline? Here are some rules of thumb.

- Haliburton County is a political construction. Its borders don’t reflect ecological boundaries.

- We should choose plants primarily native to The Land Between. These will mainly be plants from the Canadian Shield Ecozone, but we can also choose plants from the Mixedwood Plains Ecozone.

- The specific location of the garden or shoreline matters. How does it fit into the ecology of its location?

- We need to take into account that humans have altered much of the ecology here, and that a garden is a human construct.

- We also need to take into account the availability of native plants for Haliburton.

I like to think of these rules as somewhat fuzzy. They’re broad rules, but they can be broken. All we can do is our best. Any native plant is better than a non-native. Every native plant we put in the ground is a step forward because from that point on, we’re gardening for life. That’s what matters.

Simon Payn