Good Mess, Bad Mess: Using Disturbance in Your Landscape

Whenever we do something in our landscape, we cause disturbance. But is disturbance good or bad? The answer depends on what we want to achieve.

What is disturbance?

From an ecological perspective, disturbance is any event that disrupts an ecosystem. Think of a forest fire, a flood, or a storm toppling trees. Each of these events creates significant changes, often leading to a reshuffle of plant and animal communities.

When we bring the concept of disturbance into our gardens, it takes on a more hands-on meaning. Here, disturbance refers to any action that disrupts the soil, plant life, or overall garden ecosystem. This can include common gardening activities like tilling the soil, pruning shrubs, pulling weeds, or even planting.

The key similarity between ecological and gardening disturbances is change. Whether it’s a natural disaster reshaping a landscape or our trowel turning over soil, disturbance alters the existing state of things, creating both challenges and opportunities for the life within that space.

Disturbance in a native plant or naturalized garden

Once we’re aware of disturbance, we can use it (or avoid it) to our advantage.

Any act of changing the garden is disturbance. Planting – even if we’re using native plants – is an act of disturbance. It’s changing things up from where they were. Not only are we altering the composition of species, the very act of planting disturbs the soil.

Our soils are full of seeds, many of them years old. When we disturb the soil, we’re bringing seeds once buried in contact with the light, which allows them to come out of dormancy and germinate.

Similarly, when we remove plants, either to replace them with native plants or because we consider them weeds, we disturb the soil, allowing seeds an opportunity to germinate.

Plants that are adapted to disturbed sites

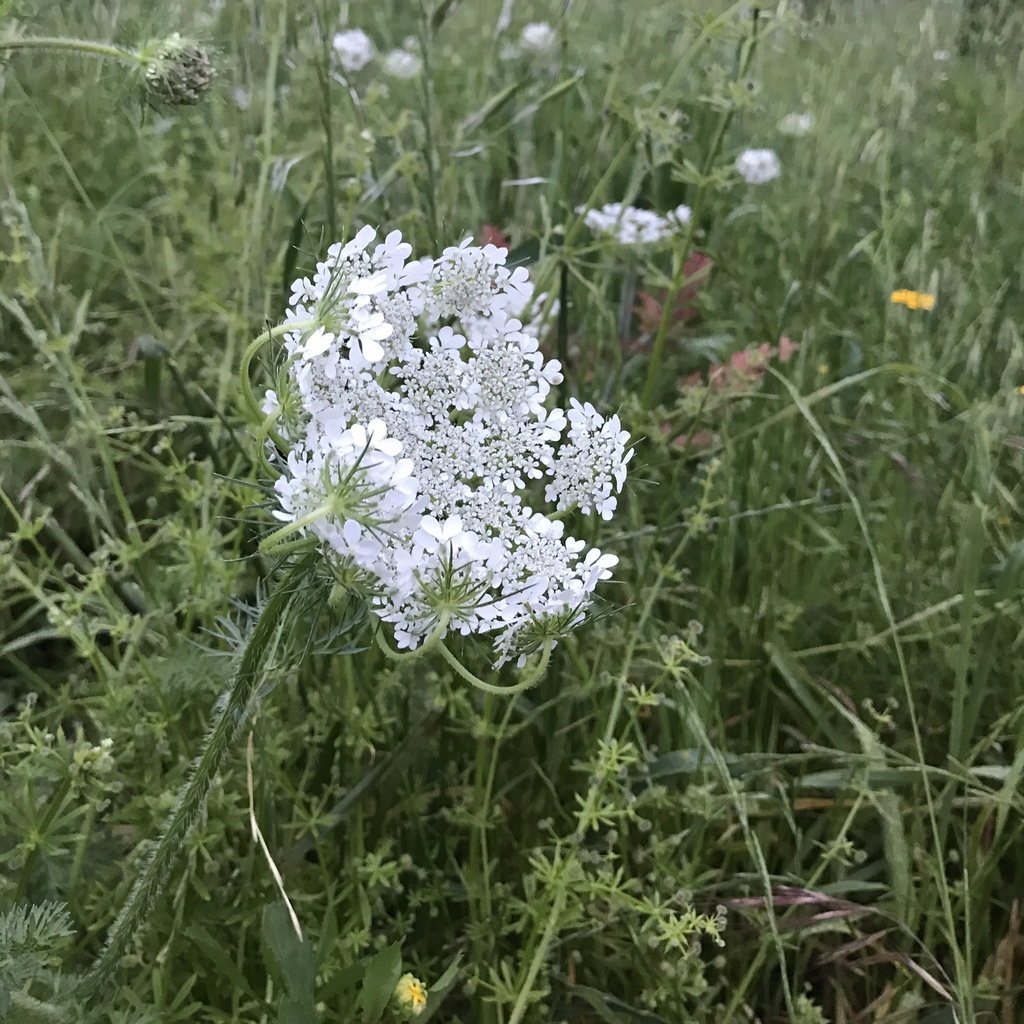

The first plants that are likely to germinate are what we consider ruderals. These are plants that specialize in colonizing disturbed sites. They have the ability to grow quickly and produce large quantities of seeds – that’s how they compete with other plants. Some are annuals, others are short-lived perennials. Basically, they live fast and die young (but have lots of babies in the meantime).

Ruderals seem weedy – and in some cases we might consider them so. But they have a place. They help stabilize a disturbed site and increase the soil’s organic content. They’re often called nature’s first responders because they heal a disturbed site.

Ruderals play a role until the longer-living stress tolerator and competitor plants take over, beginning the ecological succession process.

While there are many native ruderals (Black-eyed Susan is one here in Ontario), there are many non-native. While most non-native ruderals don’t harm an ecosystem, some are invasive. Having no natural competitors, these plants disrupt an ecosystem, out-competing other plants.

When disturbance is a good thing

If you’ve read this far, you might think that disturbance is a bad thing. It’s not necessarily.

Disturbance – for example from weather events or even from herbivores browsing – is a natural phenomenon. Fire is necessary for some seeds to germinate. A storm-felled tree increases biodiversity by opening up the canopy to light. Some plants even benefit from being nibbled by deer.

Disturbance can be useful in our gardens, too. A new garden takes some time to establish. The first plants to establish are the ruderals, giving us leaves, flowers (and providing services to nature) early on in the garden’s life. That’s why I try to include ruderals in the landscapes I plant: filling the ground with native ruderals is better than leaving bare soil for non-native or invasive quick-starting plants.

Managing disturbance in a natural garden or landscape

When creating a natural garden or shoreline, disturbance needs to be recognized, controlled and harnessed.

When I start work on a new site, I often have to remove existing vegetation. This is a huge act of disturbance. Next I dig holes to put plants in – yet more disturbance.

The result is, we have quite a disturbed, vulnerable site.

When creating a landscape, we want to work with nature to enhance its appeal to humans and the rest of nature. We try to control it, to some extent. But we also let nature be nature.

Depending on the site, it could fill up with ruderal plants, some of which we might consider weeds, if we simply left it alone. The amount of weeds that appear depends on many factors, including the nature of the site (a weedy site will have the capacity for more weeds in future due to its extensive seedbank), how much vegetation we had to remove, and whether we needed to add topsoil, which could contain its own weed seeds.

One huge secret is to plant densely. Simply put, the more densely we plant, the less room there is for weeds to pop up.

For most sites, we add a thin layer of natural mulch. This helps suppress weeds a little. But we also have to be diligent in removing weeds until the garden establishes.

But not all weeds need to be removed. Indeed, in a naturalistic garden, it’s possible that most weeds should not be removed. Because pulling weeds creates disturbance (and hence more weeds), we see that as a last resort. The only weeds we pull are those that are likely to be persistent – mostly perennial plants.

The rest, either we tolerate them or we stop them setting seed. To some extent, weeds can provide ground cover until the longer-lived plants take over. As long as they don’t set seed and create more weeds, they’re not a huge problem, other than an aesthetic one. (And I understand that it’s hard to look at a “weedy” garden.”)

It’s important to not let weeds crowd out the plants we want. It’s why diligence is required in the first couple of years. Know your plants and know when they’re suffering from competition.

Here’s one final thought: we can sometimes use disturbance to our benefit. Pruning shrubs or chopping back perennials can create more growth. Disturbing the ground and adding seed can bring more desirable plants. Indeed, some ecological restoration experts use disturbance as one of their primary tools to restore a degraded ecosystem.

The bottom line is this. Disturbance is a huge factor in our landscapes. We just need to recognize it and treat it with respect. It’s part of the dance with nature that is central to creating a natural garden.