Why ‘Good Soil’ Isn’t Necessarily a Good Thing

Poor soils aren’t necessarily a problem. Indeed, natural gardeners often prefer them. Here’s why.

What if I told you that poor soil and very dry or shaded conditions often make for a better garden? Would you believe me if I said low-nutrient, thin soil can lead to greater biodiversity and less ongoing maintenance?

A new way of looking at gardening

If you’ve learned anything about traditional gardening, you’ll have heard that plants prefer rich, fertile soil with a high level of organic content. You’ll have heard about and perhaps employed soil amendments, fertilizer and thick layers of mulch. All of this is in service of ideal conditions for quick, lush plant growth.

I admit this is a simplified view: many experienced gardeners are very aware of choosing the right plant for the right place. But it’s the view that most non-gardeners take when they think about their landscapes.

This is all well and good if you like gardening. You can get some beautiful results. If you put many species in a top-class hotel, they’ll thrive. But at the same time, it’s a lot of work and uses a ton of resources.

If you want something that is a little bit lower maintenance, it’s worth looking differently. Natural gardening is about doing things the way nature does: working with nature by choosing plants that thrive in the conditions you have rather than changing the conditions to suit the plants you want. And because nature knows best, you often get better results.

I’ve been delving into the work of two experts recently: Cassian Schmidt and Ben O’Brien. Schmidt is the leader of the “New German Style” of naturalistic planting, which focuses on habitat-based planting design. For many years he’s been conducting research at the Hermannshof garden in Germany. Ben O’Brien is a naturalistic planting designer based not a million miles from here – in Prince Edward County, Ontario. He has conducted plant trials on low-nutrient substrates.

What are stressful conditions?

While ideal conditions might be rich, organic soil with an ideal mix of sun and water, stressful conditions can be quite different. Typical stressful conditions might be:

- Woodland edge: Stress from light limitation, root competition, summer drought

- Dry open ground: Limited water and nutrient availability (for example, a septic leach bed)

- Rocky steppes: Very thin soils, limited root space (like a lot of the conditions in cottage country)

- Water margins: Stress from constant moisture

- Urban conditions: Compacted soils, heat, drought

When you think about these types of sites, it’s not hard to see how most places in Haliburton County and surrounding areas have less-than-ideal growing conditions. The good news is, there’s no need to despair – and you don’t need to change them.

(The plants should not despair, either! As Schmidt points out, plants that are adapted to what we might call stressful conditions aren’t stressed – they’re adapted to live in these conditions.)

Why stressful conditions can be better for you and your garden

There are two ways you can benefit from working with less-than-ideal conditions: Greater species diversity, and less maintenance.

Fewer resources, more biodiversity

There are two reasons why stressful conditions lead to more species of plants in any one particular area.

In rich environments with high resources, competitive plants can grow quickly and large. This leads them to shading out other plants and using up available resources. The result is that a few strong species dominate.

Meanwhile, in stressful environments with low resources, even competitive plants can’t grow too large or quickly, meaning that no single species can dominate. Plants have to share limited resources leading to more species coexisting in the same space.

Schmidt found that in dry, rocky steppes – a very stressful environment – you can have up to 50 different species in one square meter. Not all environments are quite as stressful. For example, while a woodland edge has some stress due to the level of shade, it’s not as stressful as a very dry environment. For that reason there’s less biodiversity in that site. After all, there’s a very clear link between fewer resources and more species.

Fewer resources, less maintenance

Schmidt tracked the maintenance required in various parts of Hermannshof and found that areas of stressful conditions required annual maintenance of only around 5-7 minutes per square meter versus 8-15 minutes for competitive plantings on good soil, and 40-60 minutes for traditional borders.

Similarly, O’Brien found in his trials that plots with pure aggregate were virtually weed-free in the first three years, and in those with compost three weeding sessions totaling 45 minutes was required for the whole 350 sq ft garden. Both found that after establishment, the areas did not need additional water other than natural precipitation.

While we’re always happy to have fewer weeds, there’s another upside: there’s less chance that invasive species – weed we really don’t want – will take hold.

Examples of low-resource soils

We have some wonderful landscapers in this part of the world. But many of them will admit they don’t know a lot about gardening, and certainly not about modern, naturalistic planting.

The answer to many a home or cottage owner’s woes is topsoil. Bring a load of topsoil in and you have a lovely substrate in which to plant. I’m not totally against using topsoil: a project I am working on in 2025 will need topsoil, for example, because new garden beds are being created. But topsoil comes with its own problems: you don’t know where it’s coming from and it’s likely to be full of weed seeds. The result is what seems easy to start with can lead to more weeding work later.

The thinking behind the topsoil myth is that if you bring lots of nutrient-rich, fresh soil in, you help the plants grow. Yes, maybe – but you might also be creating overly rich conditions that lead to less biodiversity and more weeds.

O’Brien’s trials were anything but perfect soil. One of his trial plots was 100% aggregates; others had a mix of aggregates and compost. Schmidt calls a low-resources substrate one that is free draining with low-nutrient conditions. These freer-draining soils facilitate storm water infiltration and resist compaction.

Plants that thrive in low-resource situations

Grime’s theory (developed by Philip Grime) is a way of categorizing plant survival strategies. He talks about three strategies: competitors, stress-tolerators and ruderals.

Stress tolerators are adapted to low resources, survive well in challenging conditions and are typically slow-growing. They are well-adapted to poor soils, shade, and drought.

Competitors thrive in rich conditions and have vigorous growth when resources are abundant, leading them to outcompete other plants. They are typically taller and have large leaves.

Ruderals are plants adapted to disturbance – for example after construction has taken place. They are annual plants or short-lived perennials that are good at colonizing disturbed ground and are typically quick to establish and set seed. In short, they live fast and die young.

Few plants, however, are purely one of these strategies: they are often a mix of two or sometimes three. It all depends on the make-up of that mix. Knowing where a plant sits helps decide maintenance strategies for a site.

Schmidt says the following survival strategies will work best for the type of landscapes in this article: Pure stress tolerators (S) and Competitive stress tolerators (CS). He says to avoid competitive ruderals (CR) as these can become invasive.

Examples of Ontario native plants that like stressful environments

I’ve been trying to classify the plants I typically used according to their C-S-R values. Information about this is hard to find, and often in German! So I tried to do it according to the plant’s characteristics and habitat requirements.

Dry and sunny stressful environments

Here, for example, are some Ontario native plants that could be considered stress-tolerators for dry, sunny sites.

Note, before specifying plants for certain sites, it’s important to make sure all other criteria fit. For example, the deep taproot of New Jersey Tea would not be suitable for a septic bed.

| Plant Name | CSR Score | Key Reasons for High S Score | Preferred Growing Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plantain-leaved Pussytoes | 10C:85S:5R | Silvery foliage, mat-forming habit, shallow roots | Full sun, dry to moist-drained soils |

| Butterfly Milkweed | 15C:80S:5R | Deep taproot, drought tolerance, non-spreading | Full sun, dry to moist-drained soils |

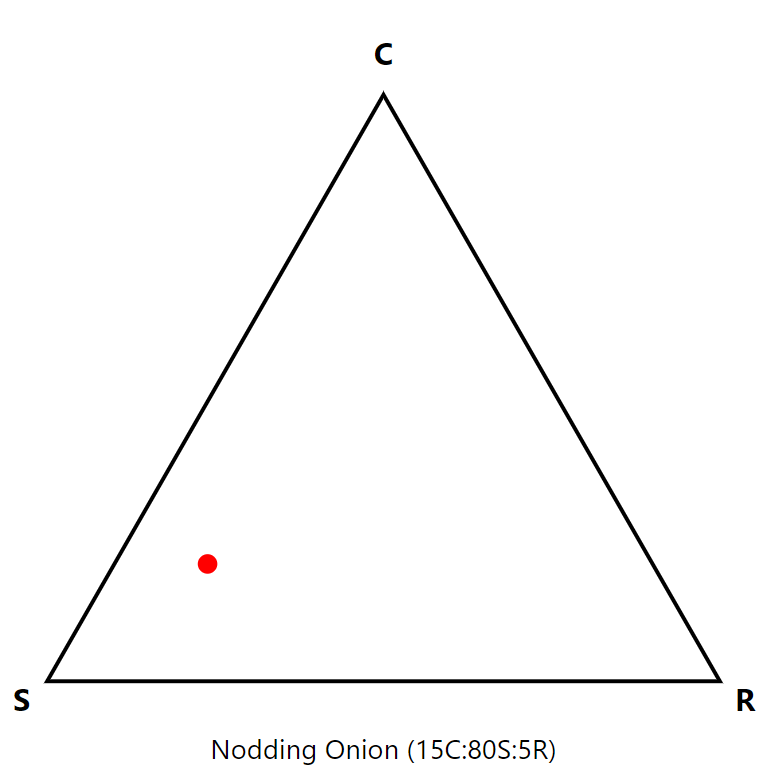

| Nodding Onion | 15C:80S:5R | Bulb storage organ, early summer bloom | Sun to part-sun, dry to moist-drained soils |

| Side-oats Grama | 20C:75S:5R | Bunch-forming habit, fibrous roots | Full sun, dry to moist-drained soils |

| New Jersey Tea | 20C:75S:5R | Deep taproot, nitrogen-fixing capability | Sun to part-sun, dry to moist-drained soils |

Here is now one of those plants, Nodding Onion, maps to the Grime’s triangle.

Part-sun, woodland edge

| Plant Name | CSR Score | Key Reasons for High S Score | Preferred Growing Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hedgehog Sedge | 20C:75S:5R | Fine-textured growth, shade-adapted | Part-sun to shade, moist-drained soils |

| Graceful Sedge | 25C:70S:5R | Delicate growth habit, shade-adapted | Shade to part-sun, moist-drained soils |

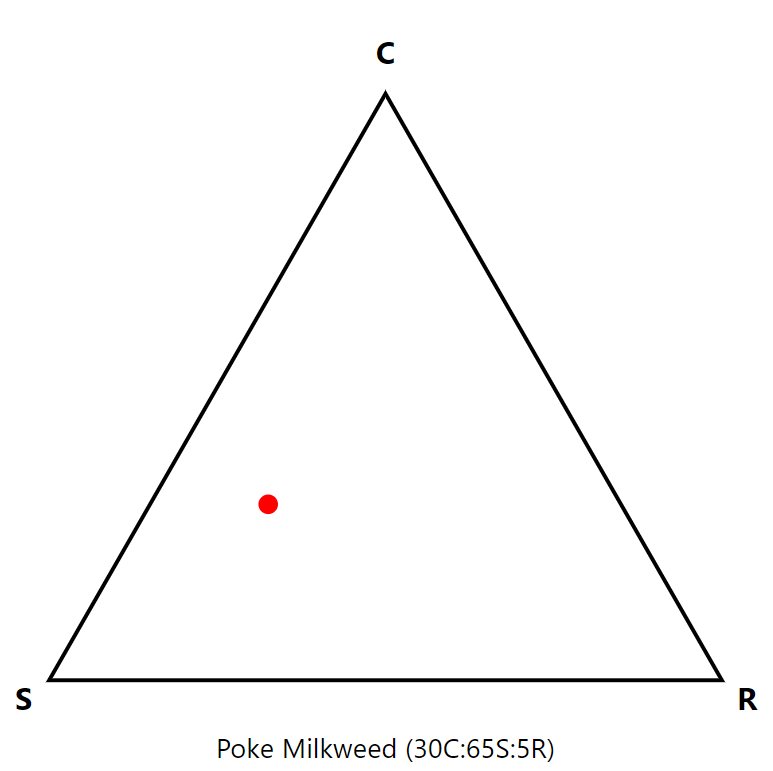

| Poke Milkweed | 30C:65S:5R | Deep taproot, shade-adapted | Part-sun to shade, moist-drained soils |

| Canadian Columbine | 20C:60S:20R | Woodland edge adaptation | Part-sun to shade, moist-drained soils |

| Long-stalked Sedge | 15C:80S:5R | Deep shade adaptation, persistent growth | Shade to part-sun, moist-drained soils |

Here is now one of those plants, Poke Milkweed, maps to the Grime’s triangle.

Thin, rocky soil

| Plant Name | CSR Score | Key Reasons for High S Score | Growing Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plantain-leaved Pussytoes | 10C:85S:5R | Mat-forming growth, silvery foliage adapted to poor soils | Full sun, dry conditions |

| Nodding Onion | 15C:80S:5R | Bulb storage organ, early summer bloom | Sun to part-sun, dry conditions |

| Butterfly Milkweed | 15C:80S:5R | Deep taproot, extreme drought tolerance | Full sun, dry conditions |

| Side-oats Grama | 20C:75S:5R | Bunch-forming habit, drought-tolerant | Full sun, dry conditions |

| New Jersey Tea | 20C:75S:5R | Deep taproot, nitrogen-fixing capability | Sun to part-sun, dry conditions |

| Cylindrical Blazingstar | 15C:80S:5R | Deep corm storage, drought-tolerant | Full sun, dry conditions |

Conclusion

There’s a lot more to natural gardening than the content of this article. This is just an example of how our approach differs from a lot of traditional horticulture. I believe however that it’s an important difference because it shifts the paradigm from one where humans shape nature to suit their desires to one in which we work with nature to provide a win-win.

This is what gardening for life is about.

Useful resources that were helpful for this article

Garden Masterclass: Cassian Schmidt – Ecology-based Maintenance

Garden Masterclass: Ben O’Brien – Growing Grit

View from Federal Twist: Cassian Schmidt – An Interview from Gartenpraxis

Wild By Design: Growing Grit